Halal is a concept that is not confined to the food or drinks that Muslims consume. Its principles govern the Islamic way of living more broadly – including the way investments are made and finances managed. As the wealth of Muslims around the world grows and those in investment become increasingly observant, the demand for Shariah-compliant assets is on the rise, along with the need for Shariah-compliant financing to acquire these.

Shariah itself is the code of conduct that guides the Islamic faith and life as prescribed in the Quran. It promotes maslaha, or a balanced way of living based on the concept of fairness, discouraging excess or injustice. Key Shariah principles in Islamic finance therefore include the prohibition of riba or interest; avoidance of gharar or uncertainties; abhorrence of debt; and abstention from haram or unlawful activities in investments or business.

Riba is highly discouraged in Islam because it is seen as creating social injustice. In a riba-based transaction, money is loaned for an intended venture and the lender is guaranteed a fixed repayment no matter the outcome. Should the venture fail, the lender typically has the right to foreclose assets or sue the borrower, who thus bears all the risks. The borrower is penalised even if they worked diligently for the venture, and this could be seen as an injustice.

Most conventional real-estate financing schemes, like other types of lending, charge interest at either fixed or floating rates with the first charge – that is the security for the loan – created on the assets financed. The amount charged constitutes riba, guaranteeing principal and interest to lenders, which is thus haram and disallowed in Islamic finance. Wealth can be increased through trade but not through merely lending money, so Islam encourages trade or investment with equal sharing of risks and returns between parties.

"Islam encourages trade or investment with equal sharing of risks and returns between parties"

Types of Shariah-compliant contract include profit-sharing models such as musharakah; or mudharabah where the lender provides funds to an entrepreneur on a joint-venture basis and the entrepreneur themselves either contributes further equity or effort. Returns and losses are then shared according to predefined ratios in proportion to capital or effort contributed. For acquisitions in real estate, the arrangement typically used is ijarah, that is lease financing, or murabahah arrangements as explained below. Ijarah entails a lender acquiring a property and then leasing it to a borrower who will make rental payments.

The next principle is gharar, which literally means uncertainty. It arises in transactions with outcomes that are not clearly defined or determined due to a lack of substance in their formation. Speculative activities such as trading in derivatives, short-term holding of equities or short selling of contracts without material business activities backing them or agreed risk-sharing are therefore prohibited. Along these lines, derivatives products such as those structured from mortgage financing instruments that arguably led to the global financial crisis in 2008 would not have complied with Shariah because they lacked actual assets backing them.

Islam views the matter of debt very seriously for the primary reason that it may give rise to riba: it makes borrowers vulnerable, and if they fail to pay their obligations they can fall into financial distress. The only types of debt allowed in Islam are qard hassanah and murabahah. In a qard hassanah loan, the borrower repays only the principal amount according to a mutually agreed schedule and money is thus given on a benevolent basis. Under murabahah, the owner of funds acquires an asset at a spot price – the current price quoted in the marketplace – and resells the same to the party that requires it at cost plus a mark-up on a deferred payment basis. While qard hassanah loans are more appropriate for parties that already trust each other, it may not be feasible for commercial real-estate transactions, so most such financing is arranged along the principles of murabahah.

Shariah-compliant investors must also refrain from haram activities, including those that involve the sale of pork alcohol tobacco weapons pornography or gambling services, or those that earn income from riba-based activities. Therefore a commercial building that is occupied by conventional financial institutions or businesses that deal in any of the above will not be a Shariah-compliant asset.

The above principles differentiate Islamic finance from conventional finance. While Shariah shapes the terms of Islamic lending, practitioners also acknowledge that the religion does not exist in isolation. If rigidly enforced rules may limit the assets suitable for Islamic investors, some flexibility is allowed to promote maslahah or balance.

Businesses that must rely on conventional loans, for example, should not overleverage themselves. Such loans should not exceed a certain threshold of a company's total assets, usually 33 per cent. As a result of Shariah interest in the US market, the Dow Jones created a benchmark that calculates this threshold from the ratio of total debt to total assets, with murabahah facilities excluded from the total amount of debt. Buildings that receive rental income from tenants undertaking disallowed activities can still be purchased by Islamic investors provided such activities do not exceed five per cent of the total income of the building.

"Practitioners acknowledge that the religion does not exist in isolation"

Real-estate assets are a popular class for Islamic investors because they can easily follow the principles of Shariah-compliant finance. They are tangible assets producing income that can be shared to enable joint venture arrangements, deferred payment contracts or murabahah schemes. Some of the iconic Shariah-compliant commercial buildings in London include the Shard, the Battersea Power Station development and the Chelsea Barracks. Others include the 10 Queen Street Place office and Unilever House in Surrey, both owned by Malaysian pilgrim fund Lembaga Tabung Haji.

Structure for compliant transactions

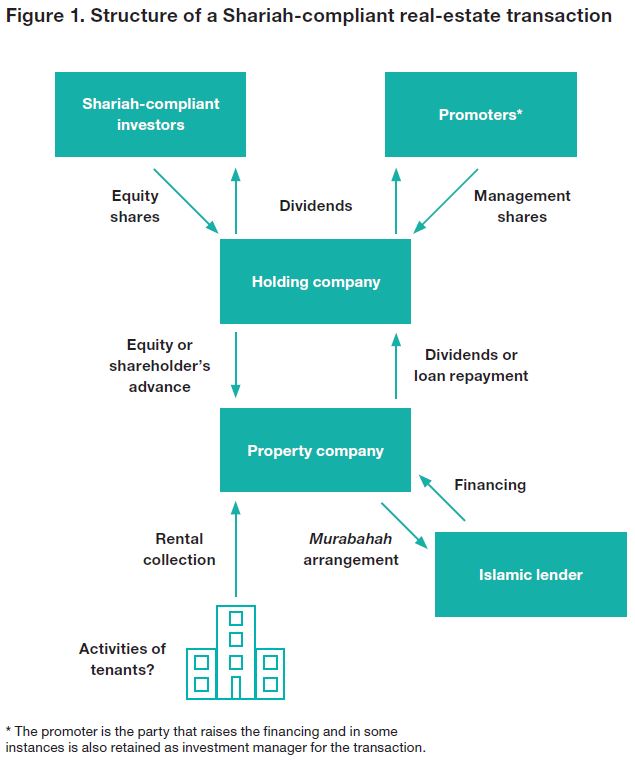

In a typical Shariah-compliant commercial real-estate transaction (see Figure 1), the first step is identifying a suitable building. The primary requirement for such assets is that most of their income must be derived from halal or permissible sources. Investors keen on that asset then agree to acquire it using Shariah-compliant financing, equity investment or a combination of these.

The investors pool their equity contribution and subscribe to shares in a special purpose vehicle set up as a holding company. Some of these may be also be issued as management shares for promoters who will manage the acquisition. The holding company is created to formalise the equity arrangement among the investors, and profits and losses will be shared in proportion to the equity contributed.

Next, a property company is established as a subsidiary to acquire the building and is provided with funds by the holding company in the form of equity injection, shareholder advance or some combination of these. The property company is then able to take a Shariah-compliant loan from an Islamic lender to raise the remaining amount required to meet the acquisition price, which is usually a murabahah facility.

In this part of the transaction, the property company will instruct the Islamic lender to purchase commodities at a spot price corresponding to the loan amount. Such commodities are purchased from platforms that form a marketplace consisting of traders and buyers. The lender then agrees to sell the commodities to the property company at cost plus a mark-up, with repayment made on a deferred basis.

The property company then sells back the commodities at spot price, making the deferred payments using rent collected from the building. The Islamic lender will place a charge on the building, meaning that they have the ability to repossess it; the commodities do not form part of the security, as they are only traded to allow the purchase of the asset. The balance of the rent collected after repayments of the murabahah facility will then be split between the investors in proportion to their equity contribution, with losses split in a similar way to ensure fairness.

One may consider that the mark-up on the murabahah loan is akin to interest in a conventional loan, and practitioners continue to argue over this contentious point. Granted, the payments or the way the amount is calculated may resemble riba arrangements. However practitioners urge proponents to look beyond the mark-up, because in the murabahah facility, the lender extends its involvement to participate in the acquisition process through the commodity purchase. The transfer of the ownership from lender to property company lends more substance to the relationship between the two parties.

Critics may also ask whether the capital markets where the asset is located lack Islamic finance lenders; Islamic loans, after al,l are hard to source in the west. In such cases, investors' equity is wrapped around the holding company as a murabahah arrangement given by a finance company set up among investors, and the property company then acquires the conventional financing to complete the purchase. Practitioners usually don't look beyond the holding company to ensure Shariah compliance, but the Shariah pronouncement issued may insist that the leverage does not exceed 33 per cent of the asset value.

As recently as two decades ago, capital market players were sceptical about the prospects or promise of Islamic finance beyond Muslim-majority countries. Conventional market players merely read about Islamic finance as a matter of interest, not as a practice to be developed in western markets. The pursuit of quality assets has, however, encouraged Islamic investment in the west and practitioners have become more optimistic about its ability to complement conventional financial products and instruments.

Related competencies include: Property funding and finance